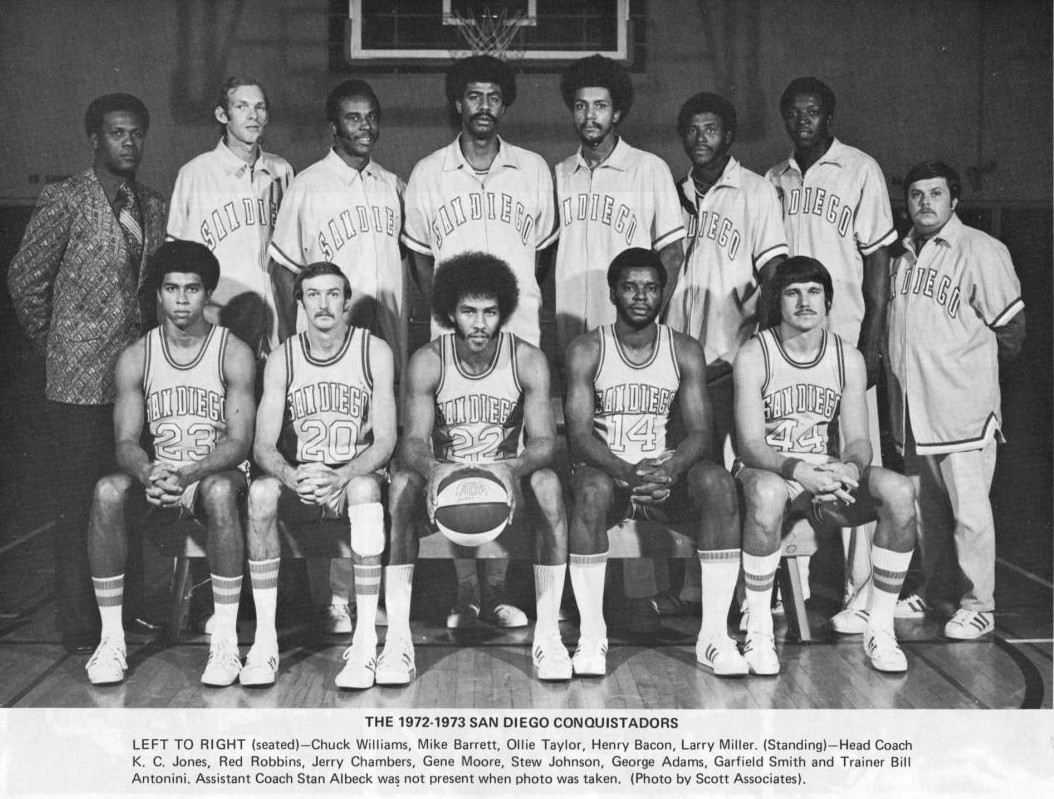

(PICTURED: THE TEAM WILT INHERITED FROM KC JONES)

Surprise was always a trademark of the Wilt Chamberlain mystique, and he pulled his biggest shocker of all in 1973 when he jumped the Lakers and the NBA to become playing coach of the ABA's San Diego Conquistadors.

As it turned out, Wilt wasn't allowed to play, because the Lakers held him to the option year of his contract. But he did coach the team, and his approach to that job tied in beautifully with his reputation as one of a kind.

Can you picture a coach who didn't spend the season in his team's home city? Chamberlain didn't. Although he kept a suite in a San Diego hotel, he commuted for games and practices from his Bel Air mansion.

Not only that, Chamberlain sometimes didn't arrive for games until shortly before tipoff.

Alex Groza, himself a former star center in the NBA, was the Conquistadors' general manager. Groza, who still lives in San Diego, recalled: "Wilt would often take a PSA plane that landed at 6:30 or 6:45, and the games started at 7:30. He had a guy pick him up at the airport to get to the games on time."

Chamberlain even missed two games, on successive nights in February, and why he did depended on whom you asked. Check the following explanations:

Groza: "He was sick."

Stan Albeck, assistant coach: "He was scouting."

Lawrence Bloom, team owner: "He was tending to company business."

Seymour Goldberg, Chamberlain's attorney: "He's around."

Of course, the newspapers played it big, and when Chamberlain reappeared, he was more than a little upset.

"I've been working hard trying to earn a living. I don't understand the concern you guys (members of the press) have for me. My mother wasn't concerned. The world has so many problems, but all the press wants to know is, 'What's Wilt doing?'

"What I was doing was between Dr. Bloom (a dentist) and myself. It's not the players' business to know."

Chamberlain also was known to miss practice and turn the team over to Albeck.

Bo Lamar was a star rookie guard that year.

"Wilt didn't always show up for practice," Lamar said from Lafayette, La., where he is a supervisor for a beer distributorship. "But we had an excellent assistant coach in Stan Albeck, so we were well-prepared."

Albeck, now basketball coach at Bradley, is in Italy and could not be reached. At the time, though, he said, "Wilt's in a learning situation, and it's too early to judge him as a coach. I interpret his turning over practices to me as a vote of confidence."

Albeck resigned late in the season to become coach at Kent State.

Obviously, there was rarely a dull moment during Chamberlain's first and last season as a coach. For the record, the Conquistadors finished at 37-47, beat the Denver Nuggets in a one-game showdown for the last playoff berth, then were ousted by the Utah Stars in six games.

Now, looking back, how does Chamberlain feel about all that happened?

When a call was placed to Chamberlain's home, the voice on the answering machine said, "Tell me who, what and where and I'll take it from there."

When Chamberlain, 53, returned the call, he led off with a shot at one of his least favorite people.

"I would have gotten back to you sooner," he said, "but some of us have to work for a living. I don't make $3 million like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar."

Chamberlain explained that he was "engaged in various and sundry enterprises." He added that he had spent four days in San Diego last week to negotiate a possible business deal.

Turning to his brief stint as a coach, Chamberlain said, "It was one of the more unexpectedly fulfilling years of my pro basketball career. I enjoyed coaching, and I think I did a decent job with what I had to work with. The ABA at that time was as strong as the NBA.

"My most embarrassing night, one of the most embarrassing memories of my life, came when we beat Denver big (131-111) in the game that put us in the playoffs. I tried to pull my guys back, but I wasn't going to hold the ball like the Knicks did the night I scored 100 points."

Why did Chamberlain leave after one season? He had succeeded K.C. Jones, who had left after the Conquistadors' first season to coach the Capital (now Washington) Bullets.

"The ABA was having (financial) problems," Chamberlain said. "They didn't know if they'd have a next year. Dr. Bloom was having problems, too.

"It was a monetary situation. I couldn't come back unless it got straightened out. Money was owed, and let's leave it at that."

Chamberlain's contract reportedly called for a salary of $600,000 a year, nearly double what he had made with the Lakers. Bloom had help from the ABA in paying it, but not enough. The Conquistadors played at Community Concourse, in the arena known as Golden Hall, and their average home attendance was 1,900.

Bloom had plans to build a 20,000-seat arena in Chula Vista, but they never materialized. He wouldn't use the San Diego Sports Arena because of a feud with Peter Graham, who operated it, so he leased Peterson Gym at San Diego State the first year before moving downtown.

"Nobody knew where Peterson Gym was," Groza said. "Even many of the students didn't. It was the same thing with Community Concourse. Neither was conducive to pro basketball."

Considering these circumstances, one had to wonder why Chamberlain made his leap from the Lakers to the Conquistadors.

"I felt it was time for me to move on," he said. "I got an interesting offer from Dr. Bloom and the whole ABA. It involved a great deal of money, and Dr. Bloom couldn't afford to pay me himself. I was ready to retire from the NBA, and I was looking to do something else.

"I played my last five or six years at over 300 (pounds). I carried it deceivingly well, but it was tough. Now I'm down to 270.

"The Conquistadors hired me as a player, and I thought I'd be free to play, but Jack Kent Cooke (who owned the Lakers) said I had an option year and made a stink about it.

"That kept me from playing one more year. We probably could have fought it, but I decided to wait a year. I've always believed in honoring my contracts."

Chamberlain was asked how he assessed his coaching performance.

"First of all, I never visualized myself as a coach," he said. "I had help from Albeck, and he was more the coach and me a figurehead. But actually, I think we had a joint operation.

"I'm not excitable, but I really got involved. I remember playing the Nets with Dr. J (Julius Erving), and we had a great deal of success against them. I threatened my players by telling them, 'If you let Dr. J dunk the ball, you'll answer to me personally. Back off 15 feet and allow him the outside shot, but don't let him go to the basket.'

"I used to shoot around with them a lot in practice. I always painted myself as an outside shooter, and I liked to show people how well I could shoot. The players got to like me and know me."

Chamberlain's last statement might be contested by some of those who played under him.

For example, he blasted Gene Moore for being overweight and said to trainer Billy Antonini, "Get him a plane ticket. He's going home." After being released, Moore said, "The majority of the team hates to see him come through the door. You could never do anything right."

But Lamar has fond memories of that eventful season.

"It was a great experience," he said. "Wilt was very knowledgeable about the game, and he taught us a lot, not only about basketball but about other things. He told us about staying in condition, playing to the best of our ability and having fun.

"He used to practice with us, too. We had three-point shootouts, and he never beat me, but he could shoot surprisingly well. He would make me go in for layups with him under the hoop, and it was a little bit frightening. He blocked quite a few of my shots.

"The players liked him. He was tough when he had to be; he got on me a couple of times, but he was always fair. It was a most memorable year."

Chamberlain talked about some of the more difficult facets of his first and last season as a coach:

"I felt from the start that Stan (Albeck) was the real coach," he said. "He never placated me, but he was willing to do whatever I wanted him to do. A lot of the press would ask him, 'Does Wilt show up for practice?' He handled it extremely well.

"People looked for it to happen (missed practices), but it didn't. I played 14 years in the NBA and I never missed anything. People really wanted to criticize because my name was bigger than the team's name.

"When I played in the NBA, there was a lot of talk about not getting along with coaches. That's not true. They can take one incident and make it sound terrible."

Of occasionally arriving just in time for games, Chamberlain said, "That would happen because you can't control the airlines. I know I played it close to the chest, but when the bell rang, I was there."

However Chamberlain graded out as a coach that one season, none of his peers could match him sartorially. He was every bit as well-dressed as the two recent clothes horses of the NBA, coaches Pat Riley of the Lakers and Chuck Daly of the champion Detroit Pistons.

"I always wore a suit or sport coat and tie," Chamberlain said. "In 1960 and '61, there were polls in Paris that listed me among the 10 best-dressed men in the world.

"I was into a lot of heavyweight dressing in the early years, and it took Hawaii and California to tone me down."

Of paying a reported $1.5-million for a home despite being a lifelong bachelor, Chamberlain said, "I've been living here close to 20 years, and when I built it, people said I was crazy. I should have done a lot more crazy things. It's probably worth 10 times as much now."

Groza told about his one visit to the Chamberlain estate.

"It was incredible," Groza said. "The place even had a retractable roof. He pushed a button and the roof went back. The whole ceiling opened up.

"The swimming pool wrapped all around the house. You could go into the pool from the sitting room without walking outside. There was a deep pit with a glass wall, and you would dive under it and go right outside.

"He had buttons for everything. He could sit in bed and punch a button and a big TV would pop out of the dresser. The place is out of this world."

Jerry Gross, veteran San Diego sportscaster who formerly worked on NBA games on ABC-TV, recalled a set of circumstances that made him a lasting admirer of Chamberlain. Gross now has his own production company and broadcasts U.S. International basketball games.

"I was sports director at Channel 8 when Chamberlain left along with sportswriter Mitch Chortkoff," Gross said. "I made the comment on a talk show that I would miss Chortkoff more than Chamberlain, because I had seen more of Mitch. It was tongue-in-cheek, but Chamberlain wasn't too happy about it.

"Two years later, I ran into Wilt and introduced him to my son, and Wilt never said a word about what I had said on the air. I appreciated that. Subsequently, he told me, 'I didn't want to embarrass you in front of your son.' He's a forgiving guy, a very sensitive person."

When Chamberlain didn't come back to San Diego for a second season, Groza took over temporarily as coach.

"We were getting ready to start the season, and we realized Chamberlain wasn't coming," Groza said. "If we had hired a coach, we would have been in violation of Wilt's contract, so I had to coach.

"When he finally retired after we had played 38 games, I made Beryl Shipley the coach. That was the third and last year of the Conquistadors. San Diego had the Sails the following year, but they folded after 11 games."

As for Chamberlain the coach, Groza saw great potential that was never fulfilled.

"Wilt would have made a great coach if he had applied himself," Groza said. "Having played under various systems in his career, he could have applied those philosophies to his own, but he didn't take the time to do it.

"Still, I've always liked Wilt. He was his own person, and he so chose to live that way."

No comments:

Post a Comment